Renaissance Man

Dominic Padua (aka Dom Chi) does many things very well, including the art of marbling. Steffan Chirazi visits his Sebastopol, CA, studio to learn more.

Oct 24, 2023

Time is an abstract. No, really, it is. In that regard, perhaps we should say that Lars Ulrich recently sat down with So What! for his 72 Seasons interview at the perfect moment. While several months after the other band members spoke about it, the album is still fresh in the memory, yet far enough in the distance to allow a more objective overview of its creative process. We even get the bonus perspective of the added dimension that playing the songs live on the M72 World Tour has created.

Perhaps most telling is that I thought we’d look to make our chat a little shorter, you know, tighten things up a bit. Yeah… right. And while print puts parameters on these things, thankfully, the web does not. So here it is, Lars in conversation about 72 Seasons, M72, and, significantly, where he’s at as a human being in the middle of all that. Get some tea and join us, why don’t you?

Steffan Chirazi: Let’s start with the rear-view perspective on the making of 72 Seasons. Looking at it now and the process it took (remote recording, Jason Gossman controlling your laptop, etc.), does it seem like some faraway crazy dream?

Lars Ulrich: I think every Metallica record has its own journey, its own story, its own path forward. They’re all unique, and I think you accept all of them. The one common thread between all the Metallica records is that they’re done with the best intent, the purest intent, and always an attempt in that moment to write the best songs to create the best collection of songs.

Then there’s a set of practicals that play a role in that at some level. So obviously, now with 72 Seasons being out a couple, what, four or five months, the record’s still very fresh to me. I like what I’m hearing. I don’t listen to it very often, but just six weeks ago, when we started the North American run in New York, there were a couple more songs that we wanted to learn. So I listened to those songs and listened to the record. I don’t think I’d heard it in six weeks, but it still sounded very fresh, weighty, and cohesive. You know, I’ve said this many times: there’s what I call the “honeymoon period,” which is when you make a record and finish a record, you put that record in your back pocket, and then you go off into the world. And at some point, you listen to that record again, and at some point, you start having some questions about the choices that were made. [For] different records at different times, that honeymoon period can be short, can be long, whatever. So, four to five months later, I still don’t have a lot of questions. I’m happy with what I’m hearing, I’m appreciative, and I like the choices that were made.

The interesting thing about this record is also – and this kind of dawned upon me as I was doing interviews for 72 Seasons in the spring – that every record, through no choice of your own, is always related to the previous record. If you like the previous record, that affects where you’re going with the next record. If you don’t like the previous record, that affects where you’re going with the next record. So, in terms of the lineage of the records, the next record is always tethered to the previous record in some way, shape, or form.

I have made no secret of the fact that Hardwired, certainly for the most part from ’16/’17 forward, has been a record that, in my ears, has aged really, really well. So, when we started the process of what became 72 Seasons, there was no radical attempt to alter the course forward because Hardwired felt like a really good jumping-off point. Obviously, the parameters were different in that we were in lockdown. There was a lot of uncertainty; the band was trying to figure out its place. And how do we pick the pieces up again? That’s already been talked about a little bit with “Blackened 2020” [the track discussed by others previously in this series - ED]. And then, during that awful and unprecedented time in lockdown, how do we make music? How do we connect to our fans and to our friends and family out there? How do we make a difference as Metallica? And that eventually led us to start writing songs and to do the stuff remotely and through computers and Zoom sessions, etc., etc., etc. Then, ending up here at HQ, masked and under many Covid restrictions. Eventually, as things got more and more “along,” the process became more and more normalized, whatever that means in the context of making a record. So, in hindsight, now the record’s been out for five months, I’m happy with it. We’ve played eight of these songs live, [and they’re] super fun to play. I think all eight songs that we played live are connecting with the audience, with the fans, maybe a few of them slightly at a deeper level than others. We’re digging what we’re doing, and as I said, the easy way to sum it up is that there are no radical red flags.

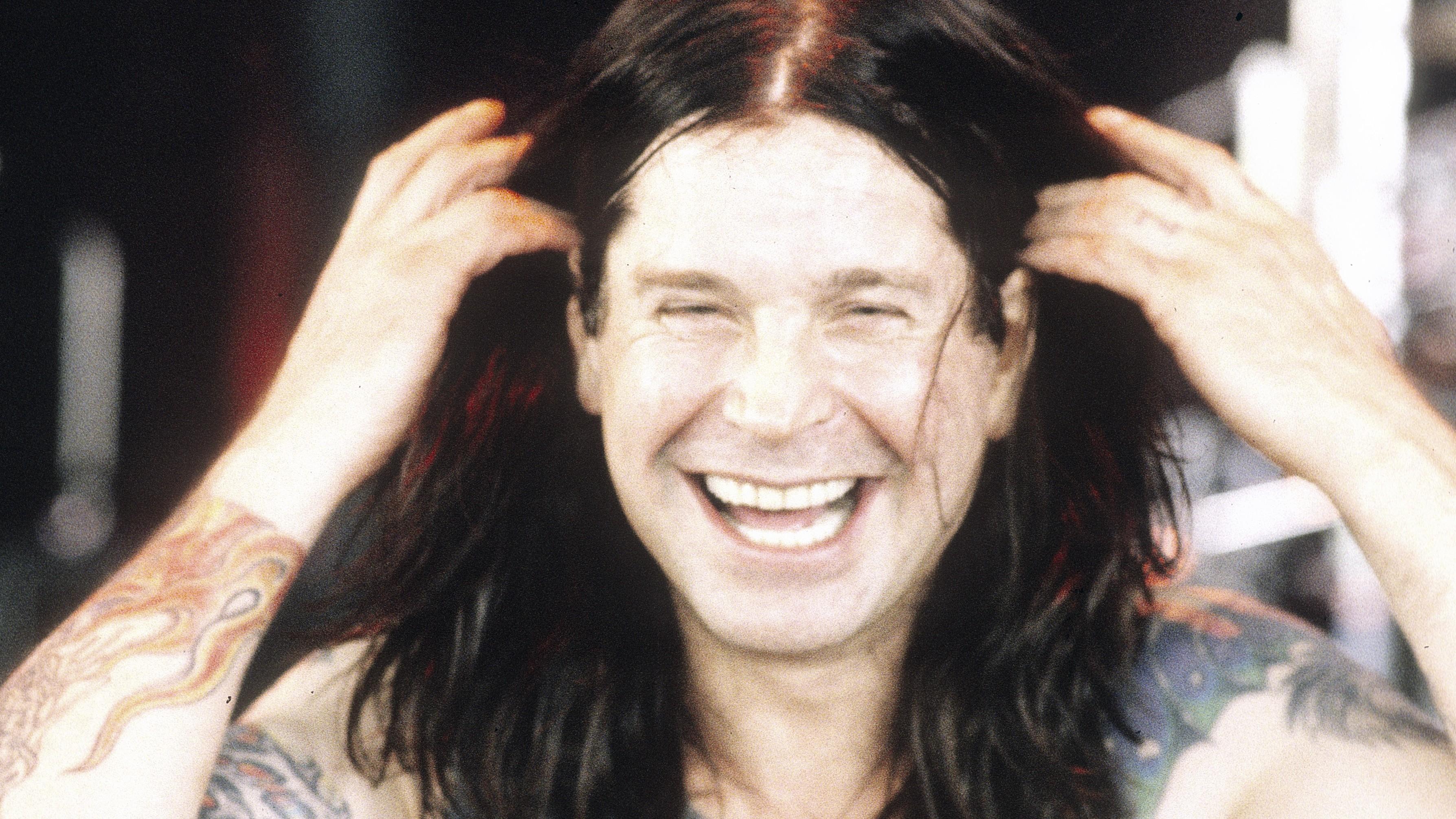

Photo Credit: Tim Saccenti

SC: One thing you have not touched on, which is extremely significant, is James. He went back to rehab and through a cycle that I think you’re very familiar with; you’ve lived it before. Where did that figure into this album’s creation and being written? Did you have fears at that time (that the band might not make it)? Do you think it was easier that you weren’t all in the same studio?

LU: That falls into the “what-if” questions, and I’m never a big proponent of the “what-if” question. “What if this happened instead of that?” Well, it didn’t. We moved forward with the situation that we’re in.

SC: But you’re a thinker; you would’ve considered this. I can’t believe you would’ve just moved on and been like, “Okay, none of that happened.”

LU: As you’re going through a process, there are two parts to it. There’s the “going through and moving forward,” and then there is the “sitting and talking about it two or three years later” and trying to figure out what spin you’re going to put on it. Those are two different kinds of things, so to walk through every emotion, or every up or down that happened to you at this point or that point, I mean, I don’t know if I have enough of a specific memory.

What James went through at the tail end of ’19 into ’20 was something where it really felt like I – and the rest of the guys in the band – had to give him the space that he needed, had to really take a step back, and just suspend everything that was on the table. We needed to do that for our friend and for our bandmate and partner. Then, slowly, the pieces started coming back together in the spring of ’20, and then everything got side-swiped by the horrific [events] of Covid and the lockdown. So, as we were giving the inner-band dynamics the time that they needed, we realized that there was no need to rush anything. And at the same time, like I said before, [we were] trying to figure out: how does Metallica make a difference, how can music make a difference, what can we do?

I still can’t get away from the analogy I’ve said a million times: you’re trying to keep the train on the tracks. You don’t want to necessarily 100% force its direction, but you want to ensure the train doesn’t derail. And when I think back on 2020, that’s kind of the overview. Obviously, there were a couple of things. There was the drive-in theater concert, and every time that we got back together, every time we would do Zoom calls or whatever, we would start understanding what headspace everybody was in and what everybody was capable of and willing to do. Also, where all the boundaries were as you were trying to move it forward.

But nothing radically different than other times that we’d been challenged in the past, so there’s a part of me that sort of just… you roll your sleeves up. You want to get back and get engaged. You accept the parameters that are put on it, and you try to make progress within those. Three years later, we have this incredible record. It’s hard to believe that a part of what lives in this record – the energy, the lyrics, the themes, production, all of it – is not somehow correlated to the challenges that were thrown our way.

Photo Credit: Brett Murray

SC: I’m going to stick on this point for a moment because I think it’s very important. I was looking at the “20 Years of Anger” exhibition in The Metallica Black Box. I remember that period as being incredibly challenging for, I guess, Metallica, but essentially for you. Equally, I remember you being “the custodian.” You just said there’s a side of you that rolls up your sleeves and just gets on with it… but that’s you, right? You take on the work to push through and to get it done. Whatever that may be. Do you think that you are someone who finds comfort in the refuge of that hard work at tough times? If you put the jacket and gloves on, and you get in there, and you steer the ship, is that your way of comfortably dealing with turbulent situations?

LU: It’s a good question. The first thought that comes to mind is that the period you’re talking about is 20 years ago; it was actually more than 22 years ago. So, at that time, it felt like we were still not far enough into it to fully accept that it could maybe derail. It felt like there were still a lot of things that had to be done, said, played, whatever phrase you want to put on it. Now, it feels like everything that we’re doing is what we do, and this is who we are. People often ask me in interviews, “What is left to accomplish?” And I go, “Well, the thing that’s left now is just sticking around!” It’s almost like you’re on borrowed time now; nobody thought that you would be doing this 40 years into your run. Nobody could fathom that when we started. It dawned upon me the other day that when we started, Mick Jagger, Paul McCartney, all these guys were still in their 30s. So, there was no road map for playing rock and roll in your late 50s, early 60s, or, in the case of Jagger and McCartney, in their late 70s and early 80s. So, everything that we’re doing now feels like it’s sort of a bonus.

The fact that we’re here, the fact that we’re healthy, the fact that we’re playing what may be the best shows of our run and having the kind of summer that we’ve had, that’s so fucking insane, and so incomprehensible based on the outlook if you were saying this in 2002, [nearly] 22 years ago. So, it feels like a different type of thing because I think there’s a much greater sense of appreciation and gratefulness for what’s going on now, where 20 years ago, it felt like an unexpected time out. Now, I think we’re much more equipped to deal with the bumps in the road and much more mentally accepting of the bumps in the road. You’re so appreciative of every element of it, and if you sit down and look… four guys at this level, just the fact that we’re functioning is a minor miracle. James and Kirk are north of 60, Rob and I are knocking on that door. It’s fucking crazy that this is still happening. So, it feels like we’re in so much uncharted territory, and it feels like rock and roll itself is in so much uncharted territory. The Rolling Stones are putting out a record next month. The Scorpions are celebrating their 60th anniversary in like a year or two. That is all so fucking crazy, so everything that’s going on just feels like a bonus.

SC: When you look back at 2002, all the work that was done, do you think when it came to 2019, 2020, 2021 that you found yourself more comfortable accepting the dysfunction that inevitably would occur in any collective that’s been together for so long? Do you think that there is a greater sense of understanding that?

LU: Yes, I think the word I’ve heard myself use often this year is “compromise.” I’ve used it before, but it feels like a more relevant part of the journey now is identifying “compromise” as an element of moving forward. Another thing is being willing to compromise. Those are two different things. And so, I think that compromise, trust, and acceptance – at least for me – comes much easier now than it did. I think I’m less suspicious of alternate ways of doing things, and I think I’m more trusting and comfortable.

I’ll give you an example. Most people know that James comes up with five incredible riffs when he’s tuning his guitar! So, there’s always this, like, “Hey, the thing you just played, somebody put an X next to that, or red star that,” or whatever. And then 12 seconds later, it’s, “Oh, my God, that could be turned into a song,” or “This is an incredible thing,” or whatever. And James would always [say] there’ll be more riffs coming along, and I’d be sitting there going, “Yeah, well, what if there isn’t? Or what if the greatest riff ever just got lost in the ether?” Now I know there are more riffs than we’ll ever be able to turn into songs. When I sit and riff-mine and try to figure out what to do with these insane riffs, if there was never another riff that was played between Kirk, Rob, and James, there’s enough material that we could turn into songs… that I could give five stars to and say there’s the seed of a song right there… than we have time left on this planet.

So, it’s like, okay, just calm the fuck down and trust. Trust in that everything doesn’t need to be a riff that’s starred, trust that you’ll be okay, and trust that if it’s not going to be “this way,” then maybe that’s just as good. It may not be a vertical movement, but horizontal movement is also fine. It's trusting in yourself, trusting in the others, trusting in Greg, trusting in the process, trusting in the energy of the universe, or whatever. And I think that there’s a lot more of that type of resilience in the ranks now and comfort in that everything doesn’t have to be sort of perfect.

The path forward is full of unexpected twists and turns. I’m not saying that you should relinquish control, and I’m not a great believer in surrendering the whole thing because I do believe that the records are the result of choices that you’re making, hopefully mostly conscious choices, but they’re also often impulsive choices. So, it’s about finding the balances. You don’t want to get stuck overthinking everything because that can put you down a rabbit hole that’s no fun to go down. When you have your own studio, you don’t necessarily have deadlines, and you don’t maybe have budgetary restrictions or whatever. So, there are some fine balances here, but certainly, I feel the head spaces are in much more, not just “healthier” places, but much more accepting, and I just keep wanting to come back to the word “trusting” places.

SC: So, who, or what, have you tethered to in terms of helping you get to this place? Is it the relationship with Greg?

LU: It’s certainly Greg. It’s certainly James. It’s certainly Kirk and Rob. But it’s also just trusting in the process. There’s a quest to make it as great as it could be, but there may not be just one “as great as it could be” destination. So, if you accept that there are many versions of “as great as it could be,” and obviously, I’m talking somewhat abstract and maybe exaggerating a little bit, but there can be many different destinations, and each one doesn’t necessarily have to be ranked in order. So, “destination three” may not be a better destination than “two” and “four.” It’s just a different landing zone. So, if the record lands here, it’s “this” kind of record. If the record lands here, it’s “that” kind of a record. But certainly, I think that Greg is the gatekeeper; he’s now 15…16 years in, so I completely trust the relationship.

I realize a lot in interviews when I sit and hear myself yapping about all the crazy things we do. I realize, for instance, the drum sound… back in the day, it was the drum sound. I would sit with Fleming [Rasmussen – producer], I would sit with Bob Rock, and… “the snare drum needs to sound more like this” or “do this” or “more top” or “more bottom” or “make it bigger” or whatever. On The Black Album, we spent five days moving baffles around, walking around a room trying to figure out where the snare drum sounded five percent better. I don’t think on the 72 Seasons project that I had one conversation with Greg about how the drums should sound. Like, literally not one. At no point did I ever sit there and go, “Hmm, what’s up with the snare drum? What’s up with the toms?” I just trusted that these drums would sound the best they could and focused more on playing them.

SC: Well, when we were off record earlier, I said it sounded like probably your most comfortable and relaxed studio performance.

LU: And that’s what Greg and I speak about. When do the drums sound the best? The drums sound the best – I hate talking in the third person – but the drums sound the best when the drummer’s not thinking about how they sound. It’s really that simple. You know, the drummer’s just playing them and letting himself loose, surrendering to just the playing, and not, “Wait, is there enough of this or that on tom number two?” So all that, at least for me, has gone out the window. But my sense is, and I wasn’t there when James was going through his guitar sounds and so on, but my sense is that the process for everybody is much shorter because Greg just knows us better. And between Death Magnetic, Lulu, Through the Never, Hardwired…To Self-Destruct, and all the different things we’ve done, he just knows more and more. So that trust is unquestioned and is just such a big part of a creative partnership.

SC: Let me throw this as a further curve; as you’ve matured in life or gotten older, do you think you’ve become unconcerned with comments on your abilities? That perhaps it’s translated into you being able to focus more on just the nature of performance versus how it actually sounds on the record? Is it fair to say that you’ve reached a point of comfort that you maybe haven’t had before?

LU: I think that’s fair to say. In this moment, yeah, I guess I’m very content with where it’s all sitting right now, and I’m also very content with where it’s been sitting in the past, but I guess the idea of somehow… I mean regret. Regret is an interesting word because there’s so much weight in that. I think as human beings, you can’t “not regret” things that you’ve done in the past. But regret does not necessarily equate [to the fact] that you wished you had changed it. So, if, as an experiment, you say, “What do you think of the sound of …And Justice for All?” Then there’s 5,000 different opinions about how the record sounds, and then you sit and go, “Do you regret this, or do you regret that?” But you can’t have The Black Album, the way The Black Album is and came to be, without the choices that were made on the …And Justice for All album. You can’t have Death Magnetic and the choices that were made on that record without St. Anger. So, it’s all tethered together in a way that makes it a useless conversation at some point. Because everything is part of a bigger picture. And I guess I am very good at accepting the journey…

Photo Credit: Ross Halfin

SC: You’ve gotten better at it. Let’s be blunt: surely, you would admit that you’ve gotten much better at accepting, you know, the idiosyncrasies of the past or the potential foibles. I think it’s fair to say this may not have happened 10 or 15 years ago in terms of “accepting…”

LU: Right, but it’s not limited to accepting the Metallica path. It’s also accepting all the other elements in my life. It’s part of a path forward, and Metallica is one of those elements in that. It’s hard to believe that in the journey of human beings as they age, that it’s not something which happens to not all, but to somewhere between a significant portion and most people. Especially when you throw children into the mix. When you are not a father, you tend to only think of yourself. And when you become a father, most of the time [you] think about your children before yourself. I’m generalizing. So, when you start thinking of others before yourself, that plays a role in how you function in a group. Because there’s a difference between functioning in a group in your 20s and functioning in a group in your 60s. And I talked about The Rolling Stones getting to the age of functioning in a group in your 80s! So, all of that’s part and parcel of moving forward on life’s journey. Without getting overly philosophical, you can’t isolate one element of the journey forward without acknowledging the rest of the elements.

SC: Oh, I completely agree. We could go on about this for another couple of hours, but I’ll bring it back to the album. I’m asking you to put yourself in the future for this question, which I know is not a favorite, but is there a moment that you think you may all look at each other and say, “Enough. We lock the door on those riff tapes. We leave them alone. There may be 300 riff tapes. We’re not going to touch them for the next project. We’re going to start from scratch,” and thus create a new revolution?

LU: I think our records rely on the physicality and also a mix between the impulsive and thoughtful, but you don’t want to end up in places where it’s all thought, reasoning, and purpose. It functions best when it’s a little bit of all that. I’ve spent a bit of time in the comedy world, and one thing that fascinates me greatly – especially with the very best comedians – is that they’ll write a bunch of material and then go out and perform that material, oftentimes, they’ll film it for a special at the end of that run. Then, the special will come out, they’ll throw all the material away, and start over again, writing a whole new set of material. I don’t know if the material in, say, Chris Rock’s ’22 special was from ’20 and ’21. It could be that some of the bits were written in ’08, ’10, ’12, or ’14. But the idea that you take it all, throw it away, and never perform it again is really interesting to me because it’s a little bit like saying, “We’re going to go out on the 72 Seasons tour and never play anything from before 72 Seasons.” Do you know what I mean? That’s interesting to me. Why [with] music do you go back and revisit the past? And in certain cases, some classic acts will only revisit the past, only spend time in the past, and new material is nonexistent or inconsequential. Those are interesting questions to me. I feel that comedy and music have a lot in common in terms of the creative things, but that’s one place where they radically differ from each other.

I guess you could argue that the Lulu record was probably the closest that we’ve come to that because, off the top of my mind, and I may not be correct, but off the top of my mind, most of the music that was behind Lou’s singing and lyrics was stuff that was given birth to on the floor, in a certainly much more spontaneous fashion than a lot of the Metallica stuff that we’ve tackled ourselves over the years. But I see no reason to do that unless there’s some sort of creative challenge or ultimatum to yourself.

SC: Let’s talk about that physicality aspect of 72 Seasons and the M72 World Tour and how it’s played into your preparation. I don’t think it’s obsequious or superfluous to say you’re probably in the best shape that you’ve been in, maybe ever. I suppose the obvious question I would have is, what has driven that? Is it knowing that you’re going to be performing these very physical songs? Is it learning what it takes to perform these very physical songs in the very physically challenging environment of the M72 stage (which we should also touch on)? Is it a greater appreciation that you’re here? I’ve never seen you fucking rehearse like this on tour. I mean, let it not be a secret. Everyone is saying they’ve never seen you practice like this. I remember it was in Texas; you were in a rehearsal till 1:00 or 1:30 AM, ruminating on who knows what.

LU: Well, I appreciate what you’re saying, and thank you. I feel good, and feeling good makes me feel good. Not to sound too silly about it, but I’ve actually arrived at a place that I really enjoy being, and it’s a place that I feel like I have the ability to maintain without driving myself batshit crazy. I’ve made some pretty conscious changes in my diet. I basically don’t drink anymore. I drank, I don’t know, probably a handful of times this year. I can tell you I haven’t had a drink since April. There’s no cosmic reason other than I like to enjoy not drinking. I had a couple glasses of champagne in April. It tasted like sugar water, and I didn’t really enjoy the taste of it. So, I’ve made serious changes to my diet. I basically don’t drink. I basically don’t do sugar, I don’t eat dessert anymore, and I don’t eat junk food. I used to allow myself [things], like, “It’s okay, I’m going, going, going, going, and now I can have a pizza. I’m going, going, going, and now I can eat this crazy dessert. I’m going, going, going and now I can allow myself a cheat day,” as they’re called. I don’t do any of that anymore. I don’t really enjoy it, to be honest with you. I don’t want to be disrespectful to pizza, but the idea of eating a slice of pizza just doesn’t do anything for me. So, I eat the same “mushy” stuff every day, and I feel very, very happy doing it.

SC: Well, you love food. I mean, you really do love food, and people should know, for the record, that you’ve put together some fantastic dinners in your time.

LU: Yes, and I still enjoy going to a place where some people take a vegetable and do something to it that nobody else has done before. But it’s limited to what somebody with a great imagination can do to vegetables. I’m sort of exaggerating, but not completely because there is truth to it. So yes, we’re fortunate enough to go to some crazy, cool restaurants, but the ones that turn me on are the ones that come more from a creative place of what can you do. I think if you look at all the creative art forms: film, painting, sculpture, literature, music, and whatever else… now food and the culinary world have a seat at that table. Pardon the pun. I think that there are so many incredible chefs and people in the culinary world who are doing amazing things, reinventing the idea of food, meals, preparations, and what can be done with it, and that’s certainly exciting.

The other element of this is I’m just really enjoying being very, very rigid with my workouts. The Peloton came to me accidentally during lockdown. I was more of a running and treadmill guy, and I started developing some knee issues during the pandemic because I was on the treadmill so much. Jess [Lars’ wife - ED] was on the Peloton, on the bike. I started doing the bike and realized that I may actually be getting a better cardio workout on it. I was enjoying it more, and maybe also feeling that the cardio workouts – as far as the legs are concerned – are more in line with keeping the legs in shape for drumming/double bass songs like “One,” etc., etc., etc. I’m also doing a lot of core stuff. I’m just really enjoying it, and I enjoy playing these shows in this stage setup so much. It’s about your headspace, it’s about your confidence, and about feeling safe out there. There are no hiding places; there are no safe zones. There’s no way to duck and cover or to take a break, so you have to be in the moment. You’re completely accessible – and therefore vulnerable – for every moment that you’re on stage. So, I guess that all the work I’m doing gives me the highest level of confidence to get through that. And it feels like there are times where I’m sitting there, and briefly, for a second, I’ll access something and go, “That’s why you do all that fucking work that you do because of moments like right now.”

We’ve played 20 shows, give or take, on this stage. I guess I was so uncertain of what it would be like to be this exposed up on stage, [for] all of us. I guess I was so… fearful is the right word, and I was so conscious of that. I wanted to make sure that I was mentally and physically prepared for whatever that would feel like leading up to it back in April. And then, in the course of that preparation, I found myself really enjoying the rigidity and discipline of it, and now I’ve stuck with it. So, we just played the second Phoenix show last Saturday – today’s Friday. I took Sunday off, but I started my workouts on Monday. I’ve worked out at the same level every day this week, even though we don’t have any shows for the next three weeks, and I really enjoy it. I’m eating the same tofu and vegetable-based mush every meal that I have all summer, nothing’s changed. And I don’t think anything is going to radically change, at least in the foreseeable future, because I feel really good. I enjoy feeling this way, and I enjoy being a little lighter and also feeling stronger on stage.

Photo Credit: Ross Halfin

SC: Let’s look at the stage for a second. When you all first saw the production live in Amsterdam, come to life from a napkin sketch, you all seemed a little taken aback. I observed that maybe until Gothenburg, there was definitely some getting used to things going on out there. When the tour moved to North America, it seemed like the combination of NFL stadiums and simply learning this stage started clicking in New Jersey, until finally, there was the tremendous crescendo moment at SoFi Stadium, which I think people would widely recognize as two of the biggest nights that this band has ever had in a venue of that magnitude. Is that an accurate perception of your journey through this M72 stage and production?

LU: I agree with the bigger picture assessment of that. It definitely lived on a napkin and in email chains on the computer for a year/year and a half. We’ve tried for so long to figure out how to tackle playing in the round in stadiums that I think there was a kind of an aloofness to the fact that when we finally tackled it, here… now… that we would just go in and play in the round in stadiums with the same ease that we played in the round in arenas for 32 years, since ’91 on The Black Album. But I don’t think we were quite prepared for, or truly understood, the size of this. The one main difference is that when we’ve played in the past, there’s always been a center point. In anything that’s round, there’s usually a center, and so most of the time, the set’s central point has been the drums. Most of it would take place in a circle with the drums in the center, and the early sketches of this [M72 production] did have the drums in the middle. Then there were some challenges presented to Dan Braun [M72 Creative Director - ED] about what would happen if that center point went away. What would happen if you did a 180 of that model? Then the whole idea of having the Snake Pit be the center point and playing around that Snake Pit and so on started coming together. But I don’t think any of us were prepared for the sheer scale of it.

So, one thing is the stadiums. Another thing is the size of the stage. Nobody really put that together, and so when we were at the Johan Cruyff [Arena] for those couple weeks in Amsterdam [opening the tour], it was just a sheer process of getting to know this setup, getting to understand it, getting to be familiar with how it would work with an audience, and more importantly, how we would work with each other. Also, obviously, the other factors: the sound, the video screens, the lights, all of it. So [we had to navigate] the practicals of moving forward, as the crew and everybody were getting more of an understanding of what’s working and what’s not working. It was pretty clear in the beginning that the sheer distance [was a point of adjustment]. If James is opposite me, he’s, like, 30-40 yards away. When you’re playing music, there’s so much about eye contact, and I could probably play just knowing where his hand is on the neck or just seeing what he’s doing with his left hand. When he’s 30 yards behind me – in a different zip code, in a different part of Europe, and behind me – that’s a challenging thing. So, all that had to be figured out and conquered. There were some changes that were made about each drum kit… starting out closer together… before eventually everybody [moved] to different corners of the stage.

SC: Acting like a charging station?

LU: Yeah. That’s a good way to put it. But also, have a conversation with Greg Fidelman about what role confidence plays in your ability to play and perform. I mean, it’s such a significant part of it. That goes all the way around, for everyone involved. I mean, it goes to every one of our amazing crew members and [to] them understanding their roles in it. From our backline guys to all the guys that are doing the visuals and the audio cues, and whether it’s Greg [Price] who does our sound, whether it’s Gene [McAuliffe] who does our video, whether it’s Rob [Koenig] who does our lights, it all moves forward in different lanes. But yes, I would agree that the North American shows, it felt like after three-four months, it was really coming together.

[Unprompted and without missing a breath, Lars addresses a question that has been raised often by Metallica fans, that of the schedule for M72, and particularly what has dictated the city choices. ]

People ask me in the meet and greets and all the time, why are you picking these cities? There’s a whole thing about the availability of venues. There’s a whole thing about what’s called “routing” [in layman’s terms, getting tons of equipment from A to B quickly - ED]. There’s a whole thing about trucking, and then if the gear’s got to go from one place to another, do you truck it, or do you fly it? It’s got to go from Europe to America. Do you ship it? Just all these crazy, practical things.

There’s a whole slew of things that I don’t need to get into, many pieces to the puzzle. It feels like we played the shows in Amsterdam, we were there for a couple weeks, and then we took a two- or three-week break. In a perfect world, after Amsterdam, we would’ve played the Paris show the following week rather than take breaks, and so on and so forth.

You learn from the schedule. Let’s just say that the schedule in North America of doing it every weekend, like clockwork Friday and Sunday, I think was/is more conducive to a higher level of consistency in the shows by merely just being in it weekend after weekend. It made the progress more noticeable and the acclimatization and comfort more noticeable. I agree with you; by the time we hit Arlington, by the time we hit LA, we were on it. We were in fifth or sixth gear, depending on how many gears you have in that particular car. And also, the venue has something to do with it. The newer venues tend to have the sides closer. If you’re playing in an NFL stadium, if there’s no running track or soccer pitch, you know? There’s all this stuff, how far away the sides are, and all these practical things I don’t need to bore you with… but certainly, Arlington, aka Dallas-Fort Worth, and SoFi in Los Angeles were – I’d say – among the best shows we’ve ever played in the whole 42-year run.

SC: Let it also be said that you’re almost playing a third show every week. There is a full rehearsal that’s going down the night before the first gig every time, right?

LU: When you play arenas, whatever it is you’re dealing with is more consistent. So, I’m sitting here looking at a plaque [Lars points up to an award on the wall - ED] that says London, The O2… Manchester Arena… Birmingham, Genting Arena, and Glasgow, the SSE Hydro. The consistency of those four venues is probably closer together than when you play stadiums A, B, C, and D. So, we’re sound-checking because every stadium has a different set of practical circumstances. So usually on Thursday, because most of these shows are on Friday and Sunday, we do a full, sometimes hour and a half or couple hours, soundcheck that really gets us situated into that particular stadium. All these stadiums just have vastly different setups. Some of them have roofs, some of them don’t have roofs. Some of them are more bow-like, some of them are outliers and have different configurations. I believe the Olympic Stadium in Montreal was built in the early ’70s, so it has a different configuration. They used to play baseball in there, so there are some different things. The State Farm Stadium in Phoenix, where the Cardinals play, has a different setup because they roll the field in and out. So, all of them have different practicalities that are really different than when you go through the arenas, which are much more consistent.

Photo Credit: Ross Halfin

SC: All right, let’s close off with this for the moment. What’s it fucking like being on one of those kits on this stage? Put yourself in the moment.

LU: Intense is a good word. It’s very, very intense. And it’s a place you have to work up to. I’m two hours in prep now, more like two and a half, I guess, between food and stretching and Peloton warm-ups and more stretching and some more stretching and some massaging and playing for 30-40 minutes. [ED’S NOTE – You got tired reading it, right? Imagine doing it!]

When we walk out on stage and play the first song, I’ve usually been playing about 40-45 minutes by that time, really working my way into a zone. But to be up on that stage and be comfortable, you have to get to a place of focus and intensity. At the same time, I think you feel quite safe up there in terms of it [feeling] like everybody’s there to share in an experience. And when it does go belly up like it has a couple times, it all feels very good-natured. There’s been a couple times where something gets left out, or this happens, or that happens, and we try to laugh across the stage and get on with it. Those moments are thankfully fewer and further between than maybe they’ve been in the past. Maybe everybody is more focused than they’ve been. But, like I said, there’s also the element of safety in that it feels like everybody’s there to share an experience.

And I will go back to the thing you had a reaction to, the words “borrowed time.” Maybe there’s a different analogy, maybe it’s more like sort of extra innings… maybe you’re on overtime, whatever. But there’s a thing about accepting who you are. You accept your strengths, you accept your weaknesses, you accept the things that can happen, and you accept the team spirit of it. There was one time in Gothenburg where there was a miscommunication about a setlist thing. I went up on stage, the rest of the band went up on stage, and the drums were not there. You accept it. Nobody gets finger-wagged. You accept that it happened. It feels, I guess, safer than it’s ever felt. Maybe post-pandemic and post-lockdown, coupled with this idea that you are not supposed to be playing this kind of music 42 years into [your career, in] your late 50s or early 60s, coupled with the fact that this kind of music is not supposed to bring this amount of people together in this day and age. Whatever angle you look at it from, that becomes a celebration, and you are appreciative of the fact that it fucking exists, functions, and can still come together like it does.

SC: Is there still a little bit of, “Fuck you, we’re still doing it whatever you fucking think”?

LU: Yes, but it doesn’t come from a posturing place, and it doesn’t come from a chest-beating place, and it doesn’t come from a middle finger kind of place. It comes more from… “Fuck, hard rock and heavy metal still connect with people at this level!” And if we’re the ones helping carry that forward, then obviously, that fills me with pride, appreciation, and gratefulness. But it certainly doesn’t come from a chest-beating kind of… “Hey, look how fucking awesome we are.” It doesn’t.

It just feels like it’s… As a believer in a type of music and as a fan of a type of music and as a proponent of a type of music, it makes me proud that it’s still happening at this level.

Dominic Padua (aka Dom Chi) does many things very well, including the art of marbling. Steffan Chirazi visits his Sebastopol, CA, studio to learn more.

What you are diving into here is my personal journal with regards to the Back to the Beginning extravaganza. Much of it was written off-the-cuff, and the sheer magnitude of the event means that even now there are still pieces of “thought” swirling in the ether and making brain fall by the hour. These recollections, emotions, and observations are shared reflectively over three separate entries after the event and are split between an initial “post-event download” and then a more chronological reflection on our time in Birmingham…