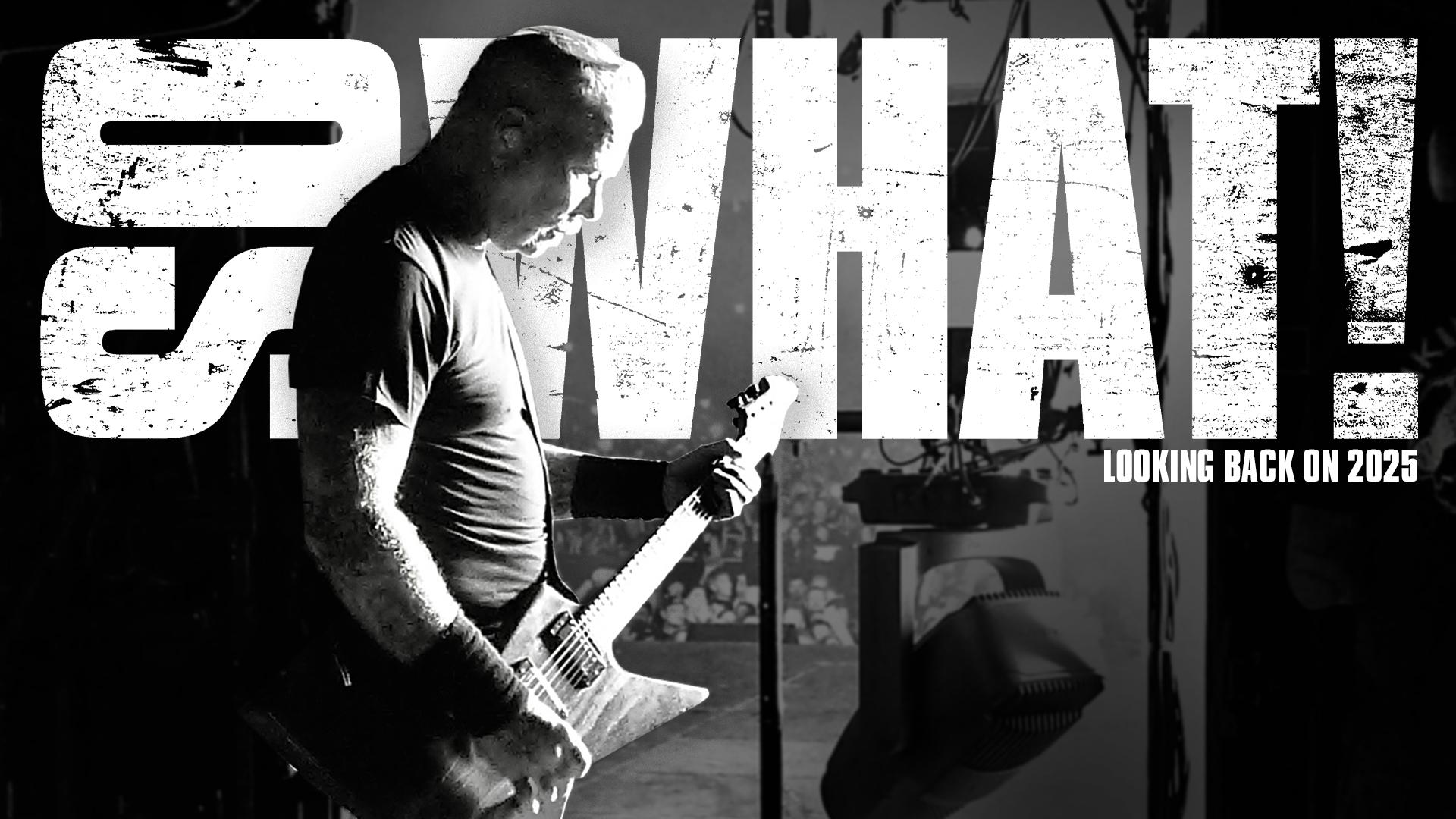

Looking Back on 2025

Some words and photos to look back on the year that was from So What! Editor Steffan Chirazi.

Apr 10, 2023

Steffan Chirazi

There is no scholarly or even literary way to introduce the conversation I had with James Hetfield in January 2023. Ostensibly to discuss the ingredients and auras of 72 Seasons from his perspective, the conversation would turn out to embrace some of the most honest thoughts and sentiments on his life and creative process that I can remember. We’ve had many discussions – interviews, I suppose – for So What! over the decades. And each one has always seen James as open as it was possible to be at that time.

This conversation, this time frame, this era of his life sees James further shedding protective gear and answering the questions with a rawer sense of self than ever before. I started to sense he was perhaps entering a new phase of self when he first opened up from the stage in South America during the spring of 2022. He spoke about how people should “not feel alone” before continuing to empathize with tens of thousands nightly about depression and anxiety; what an enormous thing to do.

I came to this conversation curiously nervous despite our long history. I knew there were important (and, at times, uncomfortable) things to ask about and discuss. No worries; we quickly found comfort and stride. One final thing before you start. After I had first heard 72 Seasons in a rough mix late in the fall of ’22, I’d been so blown away by the starkness of the lyrics, I let him know immediately. He told me he was “…excited about the turn to some more positive outlooks on darkness.”

I think we’re all enthusiastic about the evolution of this perspective and grateful for James Hetfield’s service in sharing it with the rest of us.

Photo Credit: Tim Saccenti

Steffan Chirazi: Let’s start with March 2020… The pandemic’s declared. It’s a few months after you’ve decided to take a personal step for yourself and go back to rehab. If you return to that moment in time, what do you remember feeling? Where were you in your journey, where did the world look like it was going, and what might that all have meant to Metallica?

James Hetfield: The feelings of 2020, early spring of 2020… for me, there was a rebirth again, realizing my life was needing some help. Going away to rehab, putting the halt on some band stuff again out of personal health, mental health reasons, you know? That takes priority, even though I just want to keep running and let the band just keep going and run away from problems. I needed to deal with stuff. A lot of rawness at that point. It’s really difficult when there’s so much stuff going on around you in the rest of your life to take time for yourself, to get yourself at least to a point where you feel like you’re functioning. And for me, it hasn’t been easy at times to just shut out the rest of the world.

And then, obviously, when the pandemic happened, it was – and I want to word this right because it was horrible, absolutely horrible for many people – in a strange way, it was kind of a silver lining for me. I was able to put the brakes on life and really take some time to embrace my needs at that time. So yeah, not discounting all of the terrible things that were happening at that point. It was just a timely thing that happened, and I can see the [positivity] in it for myself.

SC: A side question, I don’t know if you “journal,” I’ve never asked you that. Were you doing any of that stuff at the beginning of the lockdown? Were you getting it out in other ways than going to therapy and thinking it through?

JH: Well, yeah, therapy and program and rehabs and all that stuff. It’s all helpful for me to get some outside help around that stuff and issues from my past. As far as journaling, I’ll journal on certain struggles or topics that are going on with me. I’m not the sit-down-daily-keeping-a-diary-of-sorts. Like, “Yeah, now it’s the pandemic today, and I feel blah-blah,” there wasn’t a lot of that. But yeah, doodling and writing are certainly things that are helpful to me. Usually, when there’s downtime, lyrical things, subject matters tend to come up, obviously when we’re not focused on stuff we’ve done in the past. There’s this break, there’s a space, a white space there for new ideas and new things to come in.

SC: Those early Zoom calls that you were having, obviously beyond the ones you’re having after the first rehabs, I mean [the ones] just into the pandemic. Those ones when everyone’s trying to figure out, “Well, what do we do? Do we do live things, do we do this, do we do that?”

Did you have any fear in dealing with Metallica stuff at that point? Was there trepidation about dealing with the concept of having to do something during the pandemic, dealing with these three other people, and what your role and relationship were with Metallica at that point? Was it all something that caused you anxiety?

JH: Yeah, the downtime during the pandemic, the fear of “what does it mean to us?” We were going in to write a record anyway at some point. It’s not like we were in the middle of a tour or something… even though I guess we were. The pandemic put the brakes on everyone’s touring. I had a feeling that all entertainment was going to be taking a hiatus, and what do you do with that time? When we’re at home? Writing. It’s kind of a no-brainer.

So I was writing, I was doing stuff on my own. The other guys… the Covid virus definitely put a lot of fear into a lot of people. I think certain other guys in the band that were living more in big cities were affected by it a lot more than I was. I’m out in the middle of nowhere in a valley in the mountains. It didn’t affect the mountain life as much. Still able to get outside, hang out with a few people that you were comfortable with. Hiking, doing stuff, being able to get outside of the house at least. I know it was pretty difficult for Lars, in particular, being in San Francisco – in a city where it was a lockdown and there was tons of fear around it. You know, people were dying, and no one wanted to risk their life, which I get. For me, I didn’t feel the squeeze of it as much. And I tend to rebel against the fear of the world anyway. I create my own fears really well, really easily!

But at that point, yeah, “How do we get together? How do we start writing? What are we gonna do?” And Zoom really took off. Thank God for that because there was a connection. There was a connection while you’re sitting in your kind of self-made quarantine. Even if you weren’t sick, you were hiding. You were hiding out. And so Zoom was a great connection. Trying to figure out how can we Zoom, how can we get together, how can we do something together over that media form?

I kind of got a little annoyed and pissed. “You know what? Fuck this. What would be a great thing to reconnect the band again?” We’ve done acoustic versions of certain songs for, you know, the Bridge School, for All Within My Hands benefits, things like that. Why not take a song and just mess around with it? So I got “Blackened” – and ended up doing a couple different things with a couple other songs – but “Blackened” seemed to be something. I don’t know, there’s just something that clicked for me, and I just said, “Hey, guys, here’s a challenge. I’m going to send you something. You add onto it. You’re musicians. Let’s just embrace this challenge of isolation and connect with what we do best.”

So I just threw down – I had an acoustic mic and my regular vocal mic – just threw it down on a couple different tracks, sent it off to Greg Fidelman, our producer, and they figured out how to get it to the other guys. I said, “Hey, put whatever you feel you want to on this. Let’s have fun with this, don’t study it, don’t over-listen to it, just feel it.” And “Blackened 2020” is what happened from that, and that was the beginning of the reconnection online with our creative flow.

There are times when we’re afraid to open that Pandora’s box, the Pandora’s box of riffs, “Oh, here’s a riff.” And then once you look at that riff, there’s hundreds of other riffs. Okay, the process has started. We’re going to start writing an album. And it’s important that we’re all kind of in that same mind frame. But yeah, that “Blackened 2020” little idea/project was very healthy, I think, for all of us to reconnect.

SC: So that was like the appetizer before getting to the main course, your way of opening that Pandora’s box. That brings up something I want to ask about. Just wrestling with your place and who you are in Metallica, when you throw out something like “Blackened 2020” and say, “Add onto it,” was that your way of making sure the chemistry you’ve trusted for decades was still there? That it was all going to be okay?

JH: That is possible. You know, throwing the idea of, “Just add onto this idea I’ve got. I’ve got to do something. We need to do something here. I’m kind of spinning, going crazy here. I want to know that we’re still viable in our art form. We’re still connected.” And that started a weekly Zoom. Just a weekly Zoom with the guys. It’s interesting… it’s not me, planning something, getting something together like that. And I just said, “Hey guys, let’s get on Zoom once a week, hang out, chat with each other, see where we’re at,” all of that. That started another reconnection over the Covid break. But “Blackened 2020” in particular was, I think, an extension of my need for intuitive creation: to just stop thinking, just play, just do. Just do it. Do what God’s given you, man. So I did that and handed it off.

There has been, over the years, an unspoken crush, maybe, with Lars and I doing all the stuff - not including others. So, wanting to open those doors of creativity to other people in the band and give them a louder microphone than maybe they want. Throw that out there and say, “Do what you feel you want to do. That’s why we’re in a band.” And I think it opened the door a lot more for Kirk and Rob to be adding more ideas and running with stuff, having more input when we finally did go in to record. That is certainly something that started back, I would say, on “Blackened 2020.”

SC: There’s an unspoken reality to ask about. The times you’ve gone to rehab, rumors start. “Oh, Metallica’s going to break up. It’s never going to happen again.” And I know you have sometimes felt uncomfortable with being the object of everyone’s projections. You’re a screen for many people, an empathy point, and there’s a lot of pressure in that.

You talk about maybe finding some comfort in being able to sit still during 2020. Do you think that time was the moment you finally started to accept that “this is you”? This is what you do, this is how you speak to people, this is how you connect with them? You’ve said it a lot more recently, but I never used to hear you say it. “This is what I’m here to do.” And you said this is what God put you here to do. Do you think you’ve only really just started to trust that in the last couple of years? Is that a fair assumption, maybe?

JH: Yeah, I think [so], and also out of just sheer fear that I don’t know what else to do with my life. Playing music and being of service, going on tour, playing, writing, creating. Thank God so much for that. Because I don’t know where I’d be. So I do care for it, and I need to embrace it and accept it.

As far as other people’s worries and concerns and fears about Metallica continuing on or not, you know, I don’t feel responsible for them. But I do feel that I’m responsible for what I can do, what I can put out there. Maybe it seems egotistical to think that there are so many people relying on the Metallica record to get them through the year, whatever it is, [but] I get that it does help people.

It’s not up to me, absolutely. And I think most of the feedback around me going to rehab and all of the stuff, people’s theories, people’s ideas… what does that mean? You know, trying to figure me out. I’m still trying to figure “me” out. I mean, all that stuff’s out of my control, man. And I get [that] most of that stuff is out of fear because they want Metallica to continue. So do I. So do I, and I’m doing my best to do that, and that’s why I go away. That’s why I go and reboot. That’s just me. Embracing that part of me. And it also allows me to be more vulnerable – looking the world more in the eye and just saying, “Hey, this is how my life is. I wish it was different, I wish it was easy, I wish I didn’t have to do all the stuff, but here’s what I go through. And it brings fuel and meaning and purpose to my craft.”

SC: Well, for whatever it’s worth, I think that the whole core of this record is honesty and comfort in vulnerability and the demons that you have. And that maybe you will always have to accommodate in some way. I think it’s evident that you’ve accepted that those things are, to an extent, part of you. But we’ll get into that in a moment.

I do want to ask you: As you’re sorting and going through the “Pandora’s box of riffs” for this record – as you’re starting to put them together, with all the evaluation you’re doing at that point… Did it ever hit you that, “Okay, this is the third act in life”? Without wishing to be morbid, there’s generally three acts, right? You’ve got probably 30-30-30 in terms of years of being alive. You’re entering the third act, so maybe there’s really no time or reason to be afraid of these vulnerabilities anymore. Was that something that struck you when you were starting to put together, in your own head, what this record was going to be about?

JH: It’s interesting, the whole “fuck it” part of, “I don’t care what other people think, this is what I need to do, this is what I need to write.” Yeah, I guess there’s maybe three different phases of “fuck it”s too. The first phase of “fuck it” was, “We don’t care what other people think.” We’re just rebellious against the world. We have no idea why, but we are.

And then, in the middle ground, you’re sorting out, “What does this mean to other people?” And still having that rebellious “fuck it.” That will always be there.

I talk to a lot of older people, and there is a, “Fuck it, I don’t care what you think, I’m an old dude, I don’t care!” There is maybe a little bit of that, but at the end of the day, trying to hide what goes on in my head and in my life… you know, I have a sacred story. Everyone does. Everyone’s got one. I get to share mine, and that is a blessing. Other people get to share them in whatever ways they can, with family, with friends, with writing a book, whatever. I get to share it through music, and it gets to reach a lot of people. So I’m blessed.

Photo Credit: Brett Murray

SC: I’m gonna come back obviously to lyrical things, but let’s just talk a little music for a minute; let’s talk about [the] riffs. I noted that I thought that the actual architecture of this record was very raw. It felt very feral in the best possible way, really enjoying influences from the past, enjoying your instruments. I heard a lot of joy in the guitar playing. So talk about how you put these riffs together into the songs that they became, and talk about Rob’s role, Kirk’s role, and your role in opening the door and inviting that collaborative energy in.

JH: Yeah. A lot of – whooo – a lot of open heart surgery in a way in this album. We opened up. I was much more ready to open my heart to everyone in the band: lyrically, emotionally, and creatively. I was really an advocate, going out of my way to say, “Send in your riffs. We need stuff, c’mon,” you know? I don’t want to sit there with [only] Lars and create the songs anymore. I want everyone to be a part of it and be in it. “Can we all show up? Can we all be in the studio together? Can we jam on these things together? Can you speak up and say what you think might be great and not so great?” Really wanting to open it up, and there were challenges in that. But I think we got through most of ’em, you know?

And again, we’ve all got our own personalities for a reason, and sometimes, when you put the mic in front of someone and say, “Here you go, say whatever you want,” they realize that maybe they don’t want that and they’re better off playing off of what you come up with. And I’m the same way. Someone’ll come up with an idea. I’m good at taking that and hopefully bringing it up to the next level. So it was challenging, but it was available, and that felt very freeing for everybody.

It took longer because there were more voices, obviously, and then Greg Fidelman is a trusted outside ear. And he’s able to say, “I don’t know about that,” or, “Hey, that’s really good, do that again.” So the writing process was a lot more open and a lot more fun having all four of us here. You know, “Here’s a riff – let’s go jam on it and then see what comes up from it.” There’re so many different ways to approach writing a song. In the past, some were already kind of put together and brought to the band. This was a little more, “Hey, this riff from Manchester, it’s awesome! Let’s see what we can do with it.” So it started with less ingredients, I would say. We were building this record, and there were four chefs instead of just two.

SC: What you said about “opening the process up” is something I think would be most intriguing for people to get to grips with. You and Lars have been locked in a process for decades. I’ll ask him about it as well, but how hard was it to say to him, “Look, I need to open up. I need everyone, the other input. I don’t want it to just be me and you”?

JH: Well, I think we all have fear of change. We all have fear of change or, “Wait, this is working, let’s just keep going with it,” you know? But as an artist, as someone who’s creative, I like those challenges. I don’t like them out in the regular life very much; I don’t like changes and challenges. But in the studio, I feel comfortable with it, and I think Lars eventually understood why and where I was trying to go with it. And even if there wasn’t input from others, just having that white space for input was great.

You know, there would be times when all four would be in the studio, and Lars would be looking at me [asking], “What do you feel the next part is?” And I would just be quiet. Just say, “What do you guys think? What are you guys feeling?” It felt really free to kind of just sit back and let the process happen more. And yeah, it did take longer, and we might’ve gone through ten ideas that didn’t work to get to one that did, but if you’re not out there mining for gold, you’re not gonna find any. So there were nuggets that came out of it that were just amazing.

SC: When you look back now, do you think that the biggest chemistry element has been learning to maybe trust each other’s differences more than ever? And know that whatever someone brings to the table is vital in its own way? Perhaps it’s not so important for you all to be 25 percent, 25 percent, etc.?

JH: Yeah. I think the trust factor in each of us and the acceptance of who we are and how we go about things is becoming easier the older we get. And we all have our ways of overthinking stuff, underthinking stuff, not being prepared, being overprepared… embracing all that.

You know, we can all tend to go back to our default, or we can also pretend that “I need this, and I need to say this in this band.” And at the end of the day, it’s more important just to be heard than to actually have it happen, you know? So allowing the voice [to be heard], you learn even more about that person, and they learn a lot more about themselves. Like, “I’m pissed because I’m not getting what I need out of this band,” and then when it’s open to you, you realize that, “Wow, it’s harder than I thought…” I mean, you can’t have four leaders. You can’t. The good stuff rises to the top no matter where it comes from. That’s what I want. I want all the channels to be open so the good things can float to the top, and it doesn’t matter where they come from.

SC: The concept for the album, the “72 seasons,” essentially your first 18 years… As you’re putting these riffs together, is the lyrical side of what you’ll write for the songs also coming up? If so, are you sharing with everyone? Are you sitting down and saying, “Look, this is what I’m going to be talking about. This is what’s going to be going down”?

JH: It’s not that I’m not sharing it with them; I don’t know what it is yet.

In the past, there’s been, you know, 14 riffs, 14 song ideas. And you just kind of link them together – what matches with one thing. A lot of them are either just subject matter or potent words or maybe even a song title with nothing else. What I tried to do this time was to introduce the vocal patterns and the cadence, the intensity. What are the vocals going to be doing in this song? Trying to introduce that earlier than ever to make me feel more comfortable, and make it a part of the songwriting, so then Lars can feel where to chill out, where to go crazy, where to put certain cymbals even. I think it’s helpful for everybody to have at least an inkling of what the vocals are going to be doing. Some songs took 10 different ideas, and we would cut and paste. “The beginning of this verse is really great, but the second half of the verse in this is really great. Let’s put these together.” So I was a lot more vulnerable in not so much the lyrics, but the cadence, the vocals. That was freeing as well, and it was helpful for everybody. And then just filling in the blanks with lyrics after that, which I find really challenging and fun. It’s a giant puzzle.

SC: That’s interesting because I felt that you went out there quite a lot more vocally. The word “vulnerable” comes up again. I mean, there’s moments where it sounds like your voice is almost about to break. It actually gets almost, not thin, but it’s like you’re pushing and pushing and pushing. So you’re telling me that that cadence came before you started writing lyrics?

JH: Yes.

SC: So now I have to ask, does the cadence then inform the concept of the lyrics?

JH: Sometimes. Sometimes it doesn’t. And that’s its own challenge.

You know, fast singing is not for deep, intense words. I don’t really know how to explain how that process works… I do just want to say that I think the pandemic, being at home, getting some of these songs going home, messing with it in my own home studio made me feel a little more open [and a] little freer to try different stuff. Then I would send them in, and then people would hear and go, “Wow, you’ve never sounded like that before,” or “-done that,” and “It’s great!” Or “I don’t like it.” That’s okay. But I felt comfortable in my own room at home, being able to do that stuff instead of, “Okay, now it’s time to try these lyrics out,” and you’re sitting in a vocal booth.

So I had worked and worked and worked on these vocals and lyrics on certain notes. I mean, there’s higher singing on this record than there’s ever been. There’s “growlier” stuff. I don’t know, I felt a lot freer with just me and my microphone at home. For me, I really do address the vocals as another instrument. I’m a rhythm guitar player. I love cadence, I love percussion, I love playing drums. The vocals are another part of that percussion.

Photo Credit: Addy

SC: 72 Seasons as a concept is very intense. Let me ask you, how much of that was informed lyrically by your life as a child? And how much of it was informed by your life as the parent of children?

JH: Well, 72 Seasons as a concept, that’s been digested from somewhere else. Meaning it was a concept – it was the “72 seasons of sorrow,” and I dropped the “sorrow” part off because the first 18 years of life aren’t all sorrow. And we tend to just focus on that in our adult life, like, “I need to fix all the shit that was wrong when I was a kid.” There was great stuff as well, so 72 Seasons, everyone’s got their version of what their 72 seasons were and what they mean to them now.

Having kids definitely helps you understand your childhood and what your parents went through. More the latter. You know, me being a parent, like, “Come on, guys, give me a break. I’m just a human!” But when you’re a kid, you look up to your parents as gods. They can do no wrong, and whatever they say is what’s supposed to be. Then, when you get older, you go, “Man, I’m sorry I put you guys up on a pedestal, made you gods, and blamed you for this and that, or wished differently, but you were just humans too. You were doing your best, and you were working with the tools of your parents.”

It goes back generationally, and as a parent, really, what I want to do is maybe do it a little better than my parents did. That’s really what I want to ask of myself. There’s an inheritance of whatever they brought… you inherit some of those things. There’re some I need to work on, there’re some I need to completely forget, and there’re some I need to find. Everyone’s had a childhood. Most people I’ve met have had a childhood. Whether it’s good or bad, we can decide later on in life. You can’t change your childhood, but you can change your concept of it and what it means to you now.

SC: This is a crucial thing to bring up because when it’s being presented, even to me thus far, 72 Seasons seems like an almost dark meditation on your childhood. But what you’re saying is no, it doesn’t have to be that. It’s good and bad; it’s positive and negative. And you’re almost telling me that, in a sense, maybe you’ve sort of forgiven your parents for some of the transgressions you may have laid at their feet in previous years. That’s what it feels like you’re saying.

JH: Yes, absolutely. Hanging onto the past hasn’t served me well, but changing the narrative of my childhood has been helpful. And that’s a lifelong process, man.

SC: Yes, and I think it’s important that people understand the direction these lyrics were going for you, that they’re just a further extension of you getting your dark side out.

JH: Well, it’s interesting to contemplate, you know. “Am I who I am just because of all that? Can I change? Can I not change? Am I capable of changing? Is this just ingrained, is it in the stars? I read my astrology thing for today, and this is just how it is?” I don’t know. Nobody knows, and I certainly don’t, either.

I know the parts of me that I’d like to change take work, and it’s hard work. But I’ve got awareness of it, and if there’s some things I can’t change, that’s really not up to me as well. But the “blame” part, blaming my parents for all of this and that and whatnot, it’s got to stop. Because I have the capacity to make my own choices now. There’s a lot of psychology in this, and I can overthink all of it, but at the end of the day, is it these 72 seasons that form your true or false identity? Am I able to change or not? That’s a lifelong question.

SC: That’s fantastic. You don’t seem as afraid to address dark things, shitty things, or shitty things about yourself that you don’t like, didn’t like, and may not like in the future. Again, you seem much more comfortable with the fact that “it’s part of the whole picture, and that’s okay.” It appears to be a theme. “Chasing Light” talks to me in that way.

JH: Yeah, I guess the older I get, I realize, “All right, there’s a shelf life to me, and why would I not bare my soul in my art?” And it becomes safer and safer as I get older.

SC: But in your everyday life, too, it seems like you’re more comfortable with the fact that when that negative thing pops up for dinner as an uninvited guest, rather than lock the door, you find a way to put a plate on the table and deal with it.

JH: Exactly, yeah. Invite that demon to dinner, hang out and understand it, get to know it better. That will take the surprise or sting out of it. That demon’s not going away. I get caught up a lot in the “There’s something wrong with me. I have to change it, or else.”

SC: So does everyone.

JH: Yeah. And I think the key for me, at least what I’m feeling lately, is you learn about it. If you don’t like something, learn about it, and it will teach you something.

SC: To me, purely in terms of raw energy and lyrics, 72 Seasons feels like it’s very much a big and fully formed sibling of St. Anger in a weird way. The rawness of it and the way that those lyrics were also so raw. And I think there’s probably more pain on St. Anger than I’ve heard on any of the records you’ve put out since. Does that make any sense?

JH: Yeah, that purging, seeing “why” the pain. Also, obviously, doing a lot of soul-searching and work on self… all these lyrics have surfaced. And it makes sense to give them a place to speak, put them in certain scenarios. In certain songs, there’s a kid, there’s not a kid, there’s an adult, there’s a whatever. But to let them have a voice and to include them in me.

SC: Is it a relief to know that as you take these life lessons on board – and you maybe are not as angry about some things that you used to be – that it doesn’t mean the riffs are going to go down several watts? That, “Hey, I still bring it. I still play hard. I still can play aggressively even if I’m having an okay day and even if I’m expressing a positive emotion!” Is that a relief?

JH: I’ve always felt that. That’s not new to me. But I just realize that the chasing of happiness is kind of futile. If I’m accepting and comfortable with what I do have, then I can create the happiness there instead of keep trying to chase, chase, chase, chase. And then that also quells the fears of others that “If you’re not angry, you’re not going to make great music.” That’s kind of ridiculous. Many artists go through many phases of life. You look at paintings, you look at writings, and you either enjoy what they’re doing, or you don’t. But to be true to what’s going on inside you through your art form is important to me.

Photo Credit: Brett Murray

SC: Another side question about you and Lars – your relationship. Does he ever ask you about your lyrics? Do you ever have the proverbial “tea and biscuits” chat about them?

JH: There has not been a lot of that. There have been comments from him just saying, “Wow, these lyrics are really good,” without him going into detail about them. And nor do I do that with his drumming. You know, “When you hit the third tom in that roll, it was fantastic. I really related!” We trust each other to bring the best to the table. I think more this time, some of the feedback I got from him was, “I like this cadence better than this one.” Simple as that.

It wasn’t so much the lyrics but song titles there’s input on, and I can get wound up because Lars can name a certain song from three albums ago, and he still calls it by the working title. You know, “Oh, yeah, that’s the Black Squirrel riff.” Like, “What the hell are you talking about? Oh, you mean ‘Cyanide’?!” [Our mighty fact-checkers said that it was actually “Broken, Beat & Scarred” – ED] “Yeah. Yes, I do.” And I can take that as a slight on not wanting to include the lyrical content into that piece of art, or I can just say that’s where his head was. He remembers that riff and putting that riff in that song, and that’s where he’s at.

But when it comes to song titles, he likes to voice his opinion, and I put that out to everybody in the band. We have a little pow-wow and say, “Hey, here’s what I’m thinking for song titles. What do you think?” It’s like what we do with the artwork or the album title itself. So it is a democracy in that way. I do find that living in consultation around that is helpful. Sometimes it’s not what I want to hear, but again, we all have to deal with differences of opinion and be somewhat humble in the band. This is representing all four of us, and even more than just the four of us, we just want to make it the best. And once I understand that everyone is wanting the best, then you can throw it out to democracy. And if three people say this one’s better than this one, okay, alright.

SC: So I guess between you and Lars, it’s a little bit of, “Let’s not know or define how the sausage is made. Let’s just enjoy it.” Don’t mess with the dynamics too much because if you know too much about each other’s processes or thoughts, then the magic might disappear.

JH: Yeah. I agree with that… how the sausage is made. And I’m not really great at carrying any of that in my mind or soul. “Oh, that riff was written by him, or that song title was his…” At the end of the day, it might be important, but I don’t care, and I can’t tell you who wrote what riffs, really. And it’s fine.

SC: I’m going to go to “Inamorata” now. It’s a brilliant conclusion to the record because it almost leaves a question mark as to where Metallica is going. It’s not a conclusion; it’s a “what comes next?” the way it ends. It’s probably as close as you’ve got to a fade-out for a long time. It hangs in that way. To me, the song was lyrically your ultimate peace with discord.

Before we get into the song and how it came together, I just can’t believe that you guys wouldn’t sit at the end of hearing that, just have a chat and say, “Well, this might be one of the best things we’ve written.” I’m not saying you’d be sitting there slapping each other’s backs, but it is incongruous to me that you guys comment so little on the positive aspects of what you bring to your table. Do you think that’s ever going to change? Do you think you’re ever going to be able to say to each other, “Awesome, we’ve done a great job”?

JH: Well, it’s interesting you bring that up. The “Atta boys” or the “Congratulations, guys, we just made a fantastic record...” It’s weird. It’s like stopping in the middle of a race to say, “Man, you’re doing really well at the race here.” I mean, it’s not like it’s a race to the end, but we’re in the middle of life, you know. Lars has said to me on two occasions that we’ve made a really great record, and we should be really proud of this thing. For whatever we’ve gone through, our ups and downs, and through the pandemic and all of that stuff, we’ve made a fantastic record, and we can be proud of that. You know, musically, lyrically, art-wise, concept-wise, I think it’s pretty darn strong, and it feels great. Again, it’s another leg of the race.

SC: That actually explains things entirely – it’s a continuing journey. I’ve always said that I don’t see you ever writing an autobiography. And that if people want…

JH: …every album’s an autobiography. I’m writing my life story through the lyrics in all the albums.

SC: Yes, I think so.

Photo Credit: Brett Murray

SC: Let me ask you about the concluding lyrics to “Inamorata”: “She’s not why I’m living” and “She’s not what I’m living for.” I had to look up what “Inamorata” meant, and it actually means “your Mrs.” or “your female partner” from the Italian “innamorata”?

JH: Yeah. I mean that whole song, you know, misery as my mistress, and I’m trying to hide her. I enjoy her at certain times, but I don’t want the world to know about her. I don’t want to introduce her to the world because it’s not okay. So misery as a mistress, it does serve a purpose in my life, but I don’t want it to be my life, and I’m tired of it running my life.

SC: Powerful, powerful stuff.

Let’s switch it up for a minute and talk about the quiver of guitars that you used. Run us through the guitars that make up the sounds of this record.

JH: Yeah, the equipment used on this record… [I’m] always, always searching for better tone, always searching for a better guitar sound. And I end up with stuff I’ve used before because it just sounds the best, and that’s okay. It’s helping me speak.

There’s the Copperhead guitar, Copper Top, whatever you want to call it, but it’s the copper one that’s a snakebyte that has been painted horrendously thick and shouldn’t sound good at all. The pickups have been painted!!! It’s got the tone. It sounds great as a main guitar, so that one always gets put down first. I used it a bunch on Hardwired. The So What! guitar got some play, the EET FUK guitar showed up a lot as a second guitar.

But the guitar that probably showed up more on any of the songs besides the Copper Top was the OGV, you know? The very first guitar I played in Metallica. It’s hanging up in the control room, and I get to pick it up and play it. And with all of its nicks and damage… rings pounded holes in it, scrapes and this and that, especially on the neck, it’s just a minefield that’s been destroyed. It feels comfortable, great, it plays easy, and it sounds lively and young. So that guitar is probably never going to go away, I think. Hopefully, it’ll come with me to the grave.

SC: When you put it on… when you play it, is it like Back to the Future?

JH: It does remind me of the Kill ’Em All tour, for sure. It just does. That was the only guitar I had, so it’s got to remind me of that. But we’ve been through hell, and we’ve been through heaven together. It has definitely died a few times and come back to life. The neck’s been broken on that thing, the headstock’s come off three times, and the tailpiece just broke on this album. But it’s a survivor, like me, and this guitar has been a great friend.

SC: Let’s talk about what Tim Saccenti’s doing video-wise; how is it to have someone like him interpret these songs? What are your feelings about his interpretation so far, and what’s it like to work with his aesthetic?

JH: Hoo-wee. We’ve got a fantastic extended art family, from graphics to video shooting, concepts, ideas. Really grateful for these people in my life that help bring our ideas into a visual. I’ve always been a huge fan of graphics, visuals, logos, all of that stuff, obviously. And to have like-minded people that are able to, boy, wrangle in new, crazy stuff… I love it.

And as far as Tim, our director on these videos, I’m blown away by his vision. You go into a frigging broken-down, cold-ass, stinky warehouse somewhere in a pretty dangerous area, and you create some of the most beautiful art ever. It’s fantastic. His vision is, maybe, “Don’t make it fancy. Make it a little bit of a struggle.” Or “Let’s have a place that’s already fucked up, and let’s fuck it up some more. Whatever we do in there, it’s not going hurt it anymore.”

And I’m also blown away by how ten days ago we filmed this thing, and then here’s an edited version of it that’s going out. Done! Like what? How can you turn that around so quickly? And it is because he’s a live performer! He’s got a lighting guy, he’s got a laser guy, he’s got guys. And he’ll yell out to change the color or speed it up or something. He’s a real director calling the shots in the moment. This is not, “Oh, we’ll fix it in the post.” He’s doing a live show. He really is. So his lighting, his lasers, his vision, where the cameras are going, it’s a live show in a way, but done very theatrically.

SC: Talking about visuals and David Turner (who, along with Jamie McCathie and Ian Conklin, designed the entire 72 Seasons packaging and aesthetic). I’m going to ask you what the color yellow means to you when you see it?

JH: Yellow, for me, is light. It is light. It’s a source of goodness. So against the black, it really pops. It is light.

My vision was I wanted this album [to be] called Lux Æterna because that summed up all the songs for me, kind of an eternal light that was always inside of us that maybe is just now coming out. And I was out-voted, which is great. 72 Seasons is definitely more chewable. You get to figure out what it is. You get to dig into it and chew on it a little more. But that color came out of “Lux Æterna.”

Photo Credit: Addy

SC: Let’s talk about bringing it all on tour – 25 shows per year. You know where you’re going to be for the next two years, and you also know that these shows are going to be, I would suggest, physically challenging. Are you looking forward to that challenge, and the concepts behind the production in-the-round, in a stadium?

JH: What I know about myself is I’m an anxious guy, and before anything – filming a video, going into whatever, going on tour, coming off tour – I have anxiety about what is it going to be like. And I try to figure it out… and it’s like, stop!!!! You know, when you get there, you’re going to see your road family, you’re going to see the fans, you’re going to see what you’re doing, and it’s all going to be perfect. Just trust that when I get behind the mic, I’m good. This is what I do. But all the buildup before that is, “Oh, my God, is this going to be okay? What’s going to happen here?” and have anxiety, and that’s okay. I know that about myself. So the worry, it’s part of me. And I’m trying to not let it dominate me because I know once I’m there, it’s going to be great.

Yeah, the stage is going to be big. Going in-the-round in a stadium. Okay! We’re 59 years old. What the hell are we doing? We should be going smaller! But we love a challenge. And live, especially, we’ve got some great family members that come up with great ideas. And they all run it by us. You know, we went out recently to a stadium, and it was all marked out: what it will look like, can I get from mic number one to mic number 20 between verses or not? So there’s a lot of things that come into play with it, and it’s going to be different, and it’s going to be challenging. But having the amount of people in the Snake Pit that it’s going to be… it’s going to be fantastic. I mean, without giving away too much stuff, putting on an in-the-round show in a stadium, I don’t think has been done particularly well yet. And we’re going to try.

SC: I know we’ve discussed in the past the “masks” that you personally wear to perform. Are you now more comfortable than ever with putting that live “mask” on and enjoying it? Enjoying that side of who you are and not being afraid that, “Oh, do I look like a dick? They’re thinking that I think I’m a rock god” or whatever?

JH: I believe so. There’s less duality and more congruency with it. It’s no secret that onstage, I’m a different person, Lars is a different person. I think anyone would develop some type of survival technique to be up in front of 80,000 people. Mine has turned into more humor and more, I guess, intuition. More shooting from the hip, more embracing the unknown up there. I wish I could do that better in regular life. But if something goes wrong onstage with 80,000 people out there and I… we… screw up a lyric, or the power goes out, or somebody falls off the stage, or you screw up a song and stop it… I’m so much more comfortable. If I walk up to the mic, something’s gonna come out that makes some sense, and I won’t be paralyzed with the fear of it.

I think a lot of it has to do with being more vulnerable, being okay with who we are: a live band. We are a live band. You’re gonna see some fricking horrendous mistakes, and it’s going to be unique. But also embracing one set of eyes as well. For me, there’s a lot of times when it’s just this giant backdrop of people which I look at as one entity, one thing vibrating. When I’m able to look one person in the eyes, put a soul in that person, and identify and talk with that person at that moment, that’s helpful for me and makes it more of a reality to me. Because there’s nothing really humble about being up in front of 80,000 people, throwing shapes, people singing your lyrics, it’s fricking… it’s an experience that I can’t explain. So anything that grounds me and makes me feel like a human, such as a mistake, falling down on stage, stuff like that, it’s all helpful.

SC: To my mind, some of this must’ve started in Chile and carried on in Argentina, Brazil, and the US last year when you directly empathized with 60-, 70-, 80,000 people about how we all struggle sometimes. And to look out for each other, talk to each other, and be there for each other. When did you develop the courage to do that and to say that? What made you make that step?

JH: I can overthink it and try to come up with some great idea, but it wasn’t me. If it’s what I think you’re talking about in the middle of “Fade to Black,” there’s been a break in the song, and I would say something like, “Can you feel it?” But [I thought] let’s go a little deeper. “Can you feel it? Do you feel what I feel?” And explain a little more of the different feelings, the taboo feelings, the unworthy feelings, the feelings like, “I don’t fit in,” and “I’m terminally ill.” “I am uniquely broken, and I’m never going to be as good as you.” Let’s talk about that because we’re all here, and I feel the same. I’m up here and living my dream, but I can still feel those things. So why not? I mean, there’re times where I just feel – fuck – I feel insecure and useless out here; I don’t know what I’m doing. And saying that onstage, and people going, “Wow, okay, he could feel that during all this.” You know, “If I’m at work and feeling like I’m spinning my wheels or my life’s going nowhere, yeah, I’m not alone in that.” So, anyway… just trying to be human. Yeah, try to be human.

SC: I’d say you’re achieving that. Alright, let me close with this. What’s your greatest hope for the future?

JH: Wow. I guess my greatest hope is to continue feeling hopeful, feeling like there’s more to explore. That you don’t retire from being an artist. That no matter what happens, we’re going to be okay, no matter what. The achievements, you know, being in the Guinness Book of World Records for playing all the continents in one year, fantastic. Great stories to tell. But connecting with people, being of service, helping people through their darkness (my flashlight works, sometimes it doesn’t), and being able to say that out loud! It might be selfish, [but] it helps me stay grounded, and if it connects with someone else, I’m serving my purpose.

Some words and photos to look back on the year that was from So What! Editor Steffan Chirazi.

Dominic Padua (aka Dom Chi) does many things very well, including the art of marbling. Steffan Chirazi visits his Sebastopol, CA, studio to learn more.

What you are diving into here is my personal journal with regards to the Back to the Beginning extravaganza. Much of it was written off-the-cuff, and the sheer magnitude of the event means that even now there are still pieces of “thought” swirling in the ether and making brain fall by the hour. These recollections, emotions, and observations are shared reflectively over three separate entries after the event and are split between an initial “post-event download” and then a more chronological reflection on our time in Birmingham…